March 23, 2023

Dr. Jillianne Code, assistant professor and researcher at the UBC Faculty of Education, is featured in a documentary that follows three heart transplant patients over five years.

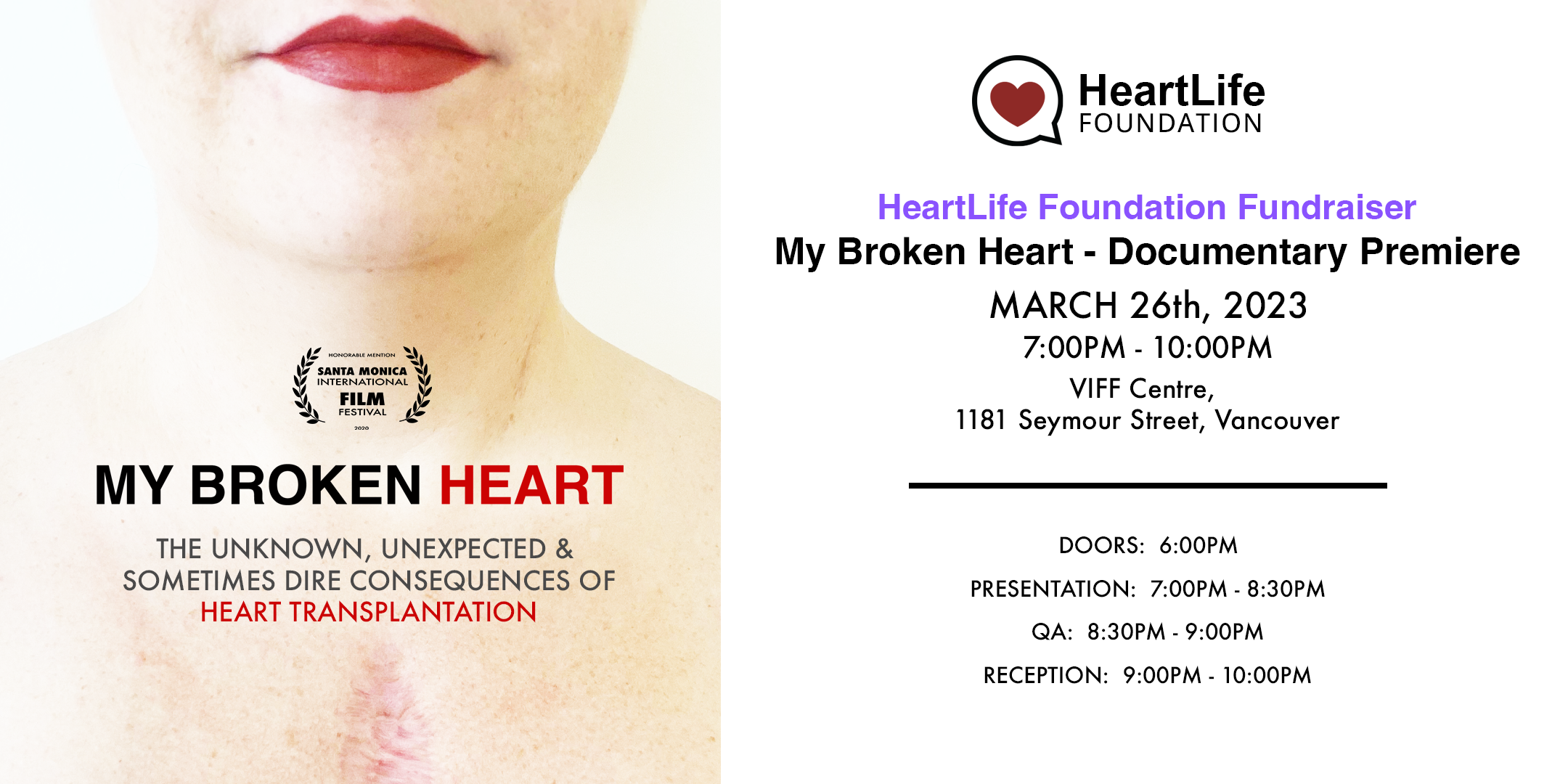

The documentary, My Broken Heart, premiers Sunday, March 26, 2023 at the HeartLife Foundation Canada Fundraiser at the Vancouver International Film Festival (VIFF) Centre in downtown Vancouver.

Just six weeks before she was to start her PhD, Jillianne Code collapsed from heart failure. Her cardiologist told her she should probably withdraw from school, but she went on to complete her doctorate in educational psychology and a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard University.

But the journey was not easy. In 2010, she experienced a stroke. Later that year, she underwent surgery for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, followed by a left ventricular assist device in 2014. She received her first heart transplant in 2014, had a massive heart attack in 2017, and received her second heart transplant in 2018.

Dr. Code is a researcher, educator and learning scientist specializing in translational research, student agency, and learning technology in the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy in the Faculty of Education at UBC.

We spoke with Dr. Code about the documentary, the HeartLife Foundation of Canada (which she co-founded), her research in the ALIVE Lab, and her advice for those facing medical disabilities.

You are featured in the documentary My Broken Heart premiering on March 26 at the HeartLife Foundation Canada Fundraiser at the VIFF Centre. What is this documentary about?

The documentary is about the journey through heart transplant and what life is like after a transplant. There’s a lot of attention around people’s journeys up to the transplant, and people often think “That’s it! You’re cured.” This documentary shows that the heart failure journey continues. It was shot over five years during some of the most trying times of my life and my husband’s life.

My husband, Dr. Nick Zap, is a PhD researcher in educational psychology, but first and foremost, he’s an entrepreneur and a filmmaker. The film was shot through his eyes.

In the film, you witness things as they happen, so there’s not a lot of room for interpretation. There’s a lot of hope that you can see. But, with that hope comes a lot of challenges. And both of those things can be true at the same time.

The documentary also features Mark Wilson, another transplant recipient. I met Mark early in my career as a transplant recipient. He was somebody who provided a lot of insight and support to Nick and me. He was always hopeful and had a positive message. Mark wanted to show that connection is extremely important for people going through this really unique journey.

The film also follows a bit of Cody Halfpenny’s heart transplant journey. Cody was just 16 years old when I met him. I connected first with his mother over social media. He was born with congenital heart issues and had a mechanical heart for three years before he received his heart transplant.

What made you decide to participate in this documentary?

One of the things that I’ve discovered through this journey is that people have different ways of dealing with life and death circumstances. When I wasn’t allowed to work anymore, I discovered a whole new voice that I didn’t know I had.

When I was on medical leave and had turned off my academic brain, I used creative writing to discover my voice, my own way of expressing what it was like to go through this journey. I went into heart failure the summer before I started my PhD. But even through heart failure, I finished my PhD and did a post-doctoral fellowship at Harvard. I created a blog called Heart Failure to Harvard to say that you can still achieve and bring these things together.

For my husband, Nick, being someone who is visually creative, filming our experiences was a way for him to make sense of what was happening, but also for us to communicate what was happening with each other. Through this film we are able to convey an important message not just about living through a transplant, but what life is like living with a heart transplant. As our journey kept going, it has become a unique and powerful story about hope and resilience.

You are a co-founder of the HeartLife Foundation—Canada’s only national patient-led heart failure organization. What is the work of the foundation?

The core work of the foundation is to connect people living with heart failure and their families and caregivers.

One of our primary goals is to engage and educate people living with heart failure, the general public, and medical professionals, on what heart failure is and how one can live with this condition.

We engage with different audiences, such as the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, the Canadian Heart Failure Society, and pharmacy and nursing organizations. We are close partners with the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and are connected with the Global Heart Hub—a global network of patient organizations that engages in international advocacy work.

HeartLife’s work is to raise awareness and change the experience of care for people living with this condition—no matter where they are in Canada. It shouldn’t matter where you live or who you are, you should be able to have the best care possible. And because I did have the best care, I strongly believe that is the reason why I’m still here. I want to make sure that kind of care is accessible to all.

How did you come to be a co-founder of HeartLife Foundation Canada?

How I became a co-founder is an interesting story. I connected with the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and attended the first-ever national roundtable on heart failure.

When I arrived at the round table, the room was full of medical professionals and only two people with lived experience of the condition were in attendance: myself and Marc Bains. We looked at each other and asked, Why are we the only two patients at the table? We knew we had to do something.

Marc had been invited to the meeting by our mutual physician, Dr. Sean Virani, who is a part of UBC Faculty of Medicine and the program director of the Heart Centre at St. Paul’s Hospital. Among the three of us, we established the HeartLife Foundation. And that’s where it started, as a way to have our voices heard.

What is the award-winning HeartLife Patient and Caregiver Charter developed by HeartLife Foundation Canada?

Our heart failure patient and caregiver charter was created to support our advocacy towards a national standard of care for Canadians living with heart failure. We began by documenting people’s journeys, showing that there’s no one single journey to heart failure and that all ages can be affected. This grew into the HeartLife Patient and Caregiver Charter. The charter outlines the rights and responsibilities of people with lived experience of heart failure, their family and caregivers and the kind of care they can and should receive.

The charter won the World Health Award – Effective Voice of the Year and has been adopted and endorsed by the Global Heart Hub and 31 international patient organizations, and it has been translated into more than 17 languages.

How has your heart transplant journey influenced your work as a researcher, learning scientist, and educator?

My journey has helped me to realize that it’s okay to be who I am. I don’t have to be an academic in one setting and a heart failure patient in another, as both of these aspects of my life contribute to my identity, and help make me who I am.

I am so fortunate that education was my chosen field because it gave me a way of understanding how to communicate and educate about what it is like to have heart failure. We started the HeartLife Foundation with the first part of our mission, to engage. Through engagement, we educate. And through education, we empower.

My journey has allowed me also to turn my focus to autobiographical and autoethnographic work. Through this work, I educate others about the experience of heart failure and of living with a chronic disease. As an academic, I have found a new line of inquiry through collaborators in the heart failure research space, and I have been able to lend my voice as a person with lived experience to research that is currently going on, especially through the Canadian Heart Function Alliance.

My work as an educator is forever changed. When I’m with my students, whether it’s my graduate students or in the classroom, I usually inform them of my experience. I see this, my own vulnerability, as a real strength. One of my superpowers is to be vulnerable and show my humanity. It breaks down the barrier between professors and students and invites students to embrace their lived experiences and their agency by showing them that I have embraced mine.

In your research you are examining the questions: How we learn? and Does technology make a difference? Why are these questions important?

Those are the original reasons that I started my PhD.

My own experience has led me to recognize that lived experiences play an essential role in how kids learn and how we learn throughout the course of our life. It has led me to want to study learner agency—or how much or how little control we have over our learning environment and how our capacity to make choices in these contexts affects our learning experience.

This has also led me to consider aspects of the design of learning environments. Understanding the role of the environment, the teacher, and the supporting role that technology can play is important. There is limited strong, sound, and rigorous research around the use of technology in education, how we should design with it, how to evaluate those designs, and in which situations we should use it. As technology keeps changing, so should our research questions.

At its essence, if we don’t understand how people learn, how can we effectively add technology to the mix? I’m trying to find ways to balance and provide empirical evidence of when to use technology and when not to. How can we design so that we are using technology to support learning? How do these designs support learner agency?

You are the director of the ALIVE (Agency for Learning in Immersive and Virtual Environments) research lab. Can you tell us a bit about a couple of the many ongoing projects happening in the lab?

Learner agency is a cornerstone of our work; as agency is the power to originate action, much of our work is centred around how much or how little agency is afforded to learners in various educational contexts.

From a philosophical stance, agency is associated with free will and how much will you have in any situation. As a learner, it’s about how much of your agency or power you have in different learning settings. At the ALIVE Lab, we are looking at how we can design environments that support students throughout their learning journey.

One of our ongoing projects is ALIVE Investigator. Through both a SSHRC Insight Development and a SSHRC Insight Grant, we have developed ALIVE Investigator as a mobile game-based environment designed around an ecological problem that middle school students are meant to solve. We are examining whether different types of game-based feedback help students problem-solve in real-time. We are using learning analytics to further examine students’ in-game actions, what decisions they make in-world, and whether this can provide insight into their agency for learning in this context. We are getting ready to take it into schools now.

Another project on which I am collaborating, along with Dr. Andrea Webb and Dr. Erica Machulak from a partner organization called the Hikma Collective, is a SSHRC Partnership Engage project called Beyond the Academy. We are investigating the professional agency and experiences of recent doctoral graduates. Our team is examining the different career trajectories that a PhD graduate can take, the role their community of practice plays in whether they find their work meaningful, and what it means to them to be a scholar.

What advice do you have for someone living with chronic or life-threatening condition?

My advice is to reach out for support. Know that you’re not alone. There are groups and individuals who have gone through something similar. I’ve discovered that living with a transplant is a chronic condition, so learning from other transplant recipients is essential.

For people working at UBC who have a condition and are struggling to balance their work and their life, one of the best things I ever did was reach out and connect with UBC’s WorkLife program.

Reaching out is the most important thing you can do.

For tickets, visit HeartLife Fundraiser: My Broken Heart – Documentary Premiere.